Football is undergoing a profound transformation, not only in the pitch, but in the boardroom. As traditional club models struggle under mounting financial pressure, private equity and investment funds are stepping in, redrawing the sport’s economic map. This article is the first part of a series, “Private Equity in Football: A Game-Changer or a Risky Bet?”, exploring how football is becoming less a community pastime and more a financial product, driven by asset valuation, commercial growth, and brand leverage. The implications are vast, raising a central question: is this the future of the game, or the start of a deeper identity crisis?

Football’s Growing Financial Instability

In the past decade, the operating costs for elite European football clubs have skyrocketed. These costs would include player wages and staff salaries, transfer fees, administrative and operational costs, stadium operations and maintenance, matchday expenses, training facilities and youth academy. According to Deloitte’s Annual Review of Football Finance, Premier League clubs’ total wage expenditure increased by 10% and exceeded £4 billion for the first time during the 2022/2023 season. During the same period, although revenue grew by £603 million, surpassing the £377 million increase in wages, rising salary expenditures and higher amortisation costs still drove a 14% increase in pre-tax losses across Premier League clubs, totalling £685 million. This surge in wages, driven by higher player salaries and lucrative contracts, has been a key factor in the escalating costs faced by clubs. Also, Premier League clubs saw their operating profits (excluding player trading) decline by 18% to £393 million, as overall operating costs rose to approximately £1.6 billion, partly due to inflation. Meanwhile, net debt increased by £473 million, rising from £2.7 billion to £3.1 billion in 2022/23, as a result of ongoing investment in infrastructure projects.

Additionally, transfer fees have also seen a dramatic rise. For example, the record transfer fee for a player in 2022 was £200 million, paid by PSG for Neymar Jr, highlighting the ever-increasing amounts clubs are willing to pay for talent. This inflation in transfer fees raises concerns about the financial sustainability of clubs. The gap between leagues is widening, with clubs in the English Premier League enjoying significantly greater financial resources than many of their European counterparts.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a severe economic downturn for many football clubs, particularly in terms of matchday revenues. UEFA’s Financial Report revealed that the combined net losses of European clubs exceeded €7 billion (£5.95 billion) during the COVID period (2020 and 2021), with clubs in Serie A and La Liga experiencing some of the largest deficits. The main factors behind this significant loss include a sharp decline in matchday revenue due to empty stadiums, resulting in an estimated €4.4 billion (£3.74 billion) shortfall, alongside reduced commercial and sponsorship income, projected to fall by €1.7 billion (£1.45 billion). Broadcast rights were also slightly affected, contributing to nearly €1 billion (£850 million) in additional losses. The COVID-19 pandemic also affected national associations, as UEFA allocated €236.5 million (£201 million) to support its 55 member associations in overcoming the challenges brought about by the pandemic.

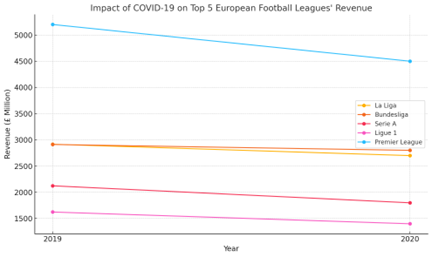

During the 2019/20 season, the financial impact of COVID-19 hit Europe’s top football leagues hard. According to Deloitte, Premier League revenues dropped by 13%, from £5.2 billion to £4.5 billion, leading to significant projected losses. Germany’s Bundesliga saw a more modest 4% decline, falling to £2.8 billion. In Spain, La Liga revenues decreased by 8% to £2.7 billion. France, which cancelled its season entirely, recorded a 16% drop to £1.4 billion. Meanwhile, Italy’s Serie A experienced the sharpest fall, with an 18% reduction in revenue to £1.8 billion.

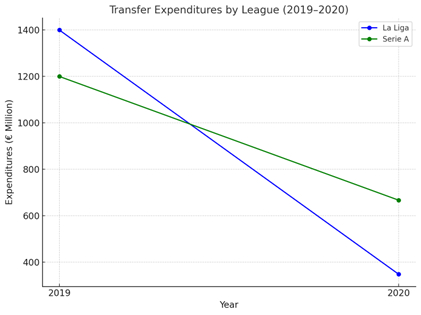

This crisis also impacted the 2020 summer transfer window where clubs in Serie A and La Liga dramatically reduced their expenses on the market. As per CIES Football Observatory, La Liga’s expenditures went from €1.4 billion (£1.19 billion) in 2019 to €348 million (£296 million) in 2020, whereas Serie A’s expenditures declined from €1.2 billion (£1.02 billion) in 2019 to €667 million (£567 million) in 2020.

These financial challenges questioned the business models of football clubs. It forced many of them to seek new sources of capital, and private equity funds increasingly saw football as a lucrative, albeit risky, opportunity. Historically, football clubs were often financially self-sustaining, relying on revenue from matchdays, local sponsorship deals, and fan ownership models. However, the rise of elite clubs with billionaire owners and global sponsorship deals has placed increasing pressure on traditional clubs. The ability to compete at the top level now requires significant capital injection, something community-based models can no longer support at the highest levels of competition.

Emergence of Investment Funds as new power players

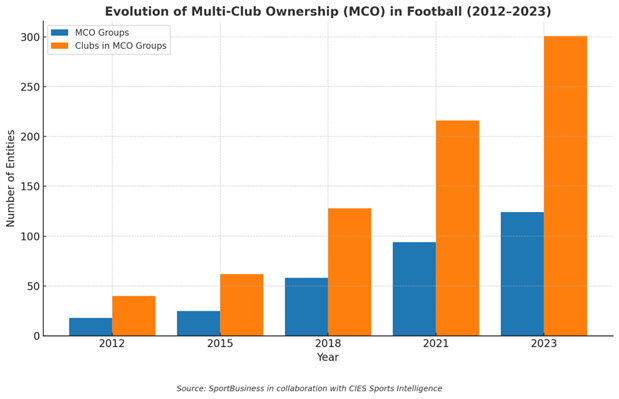

Private equity firms have become key players in the global football market. For instance, RedBird Capital Partners, CVC Capital Partners, Silver Lake, and 777 Partners have all made significant investments in football clubs across Europe. These new players of the game are defined as Multi-club Ownership (MCO). UEFA distinguishes between multi-club ownership, where a single entity exercises control or decisive influence over multiple clubs, and multi-club investment, which involves financial stakes without direct operational control. In recent years, the expansion of multi-club networks has accelerated dramatically.

Multi-club ownership is not a recent innovation. As early as the 1990s, ENIC (English National Investment Company) began acquiring stakes in clubs like Tottenham Hotspur, Rangers FC, Slavia Prague, and AEK Athens, viewing football primarily as an investment vehicle. Then the model evolved further with Red Bull’s acquisition of multiple clubs as a marketing strategy, and later with the emergence of City Football Group (CFG), widely seen as the first structured and strategic example of modern MCO. CFG’s global portfolio now spans 13 clubs across five continents.

What began as a niche investment strategy has evolved into a global phenomenon, with over 125 active MCO groups now overseeing approximately 380 clubs and more than 13,000 players worldwide. The growing trend of multi-club ownership is one of the key strategies private equity firms are using to maximize returns. This highlights the growing presence of funds in football and their consideration of this industry as a strong financial asset.

What This Means for the Future of the Game

Shift from Community-Driven to Capital-Driven Football

The influx of private equity into football is shifting the sport from its traditional roots of community-based clubs to a more capital-driven model. Investment funds are less concerned with preserving local identity and more focused on financial returns. This has led to the professionalization of club operations, but it also raises concerns about the loss of the community spirit that football once embodied.

MCO models often reduce historic clubs to assets within a broader commercial portfolio, clashing with traditional values of community, identity, and local heritage. Football clubs were founded to serve local communities, not as vehicles for franchising or profit maximization. Moreover, the financial return on MCO investments remains questionable. Developing effective player pathways across clubs is rare, and maintaining competitiveness demands substantial ongoing investment. For many, the model’s long-term sustainability remains uncertain.

Optimized Management and Operations

European professional sport finds itself at a structural crossroads. Football clubs are cultural cornerstones, deeply rooted in their communities, yet many remain persistently unprofitable. In most industries, unviable companies are allowed to fail; in football, emotional attachment makes failure almost unthinkable. This sentimental value, however, hides a troubling economic reality.

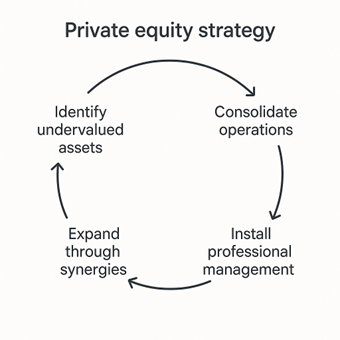

In 2022, more than 55% of European clubs recorded net losses, even amidst a post-pandemic rebound. The multi-club ownership (MCO) model introduces a rational business structure, by applying the classic private equity strategy. This framework consists of:

With private equity in control, clubs have become more professionally managed, with a greater emphasis on optimizing revenue streams and controlling costs. This includes cutting unnecessary expenses, maximizing commercial partnerships, and focusing on financial return. The implementation of data-driven decision-making has also become more prevalent, as investors push for better tracking of financial performance, KPI’s and revenue maximization. More than a growth engine, this approach is increasingly seen as a lifeline for long-term sustainability.

Potential Risks

The key risk in this transition is the potential for football clubs to lose their core identity. It might prioritize shareholders over supporters. The community-driven aspect of football, where supporters’ passions and traditions partially influence club’s decision-making, may be replaced by a financial model where profit maximization is the main objective. This could result in a short-termist mentality, where clubs prioritize quick returns rather than long-term success, potentially harming the sporting side of football.

Despite its financial appeal, the multi-club ownership model presents significant structural and cultural challenges. Clubs under shared ownership may struggle to preserve their individual identity, risking a dilution of heritage and fan loyalty. The challenge lies in balancing the competitive ambitions, history, and identity of each club within the group. It is imperative that each club within the group remains ambitious, both to support player development at the highest level and to ensure fans continue to see the best version of their team.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, the rise of multi-club ownership is set to accelerate, as more investors aim to diversify their assets and exploit operational synergies across affiliated clubs. However, this growing concentration of ownership is already drawing scrutiny from governing bodies like UEFA, particularly around issues of competitive integrity and potential conflicts of interest. However, if this model is successful, it might not remain exclusive to football, it could pave the way for broader adoption across other professional sports as part of a global multi-sport ownership trend.

Is the increasing influence of private equity in football inevitable, or are we witnessing the beginning of a dangerous revolution that could undermine the sport’s heritage? This question remains central as football continues to evolve under the pressure of financial imperatives. In the next article, as part of this series about private equity in football, we will take a closer look at the emergence of MCO’s and examine how they view football as a vehicle for long-term value creation, brand expansion, and strategic portfolio diversification.